BVH Acceleration Structure (Part 1)

Path tracing millions of spheres in CUDA

Motivation of this post

In the previous post series our path tracer could only handle scenes that fit in constant memory. In this post we are going to investigate what it takes to render millions of objects. To do that we’ll have to store the scene in global memory and use some acceleration structure to improve the performance of the renderer.

We are going to change the renderer to only support spheres of radius 1 with a single Lambertian material used by all spheres. This will help us focus our performance analysis on the ray-scene intersection.

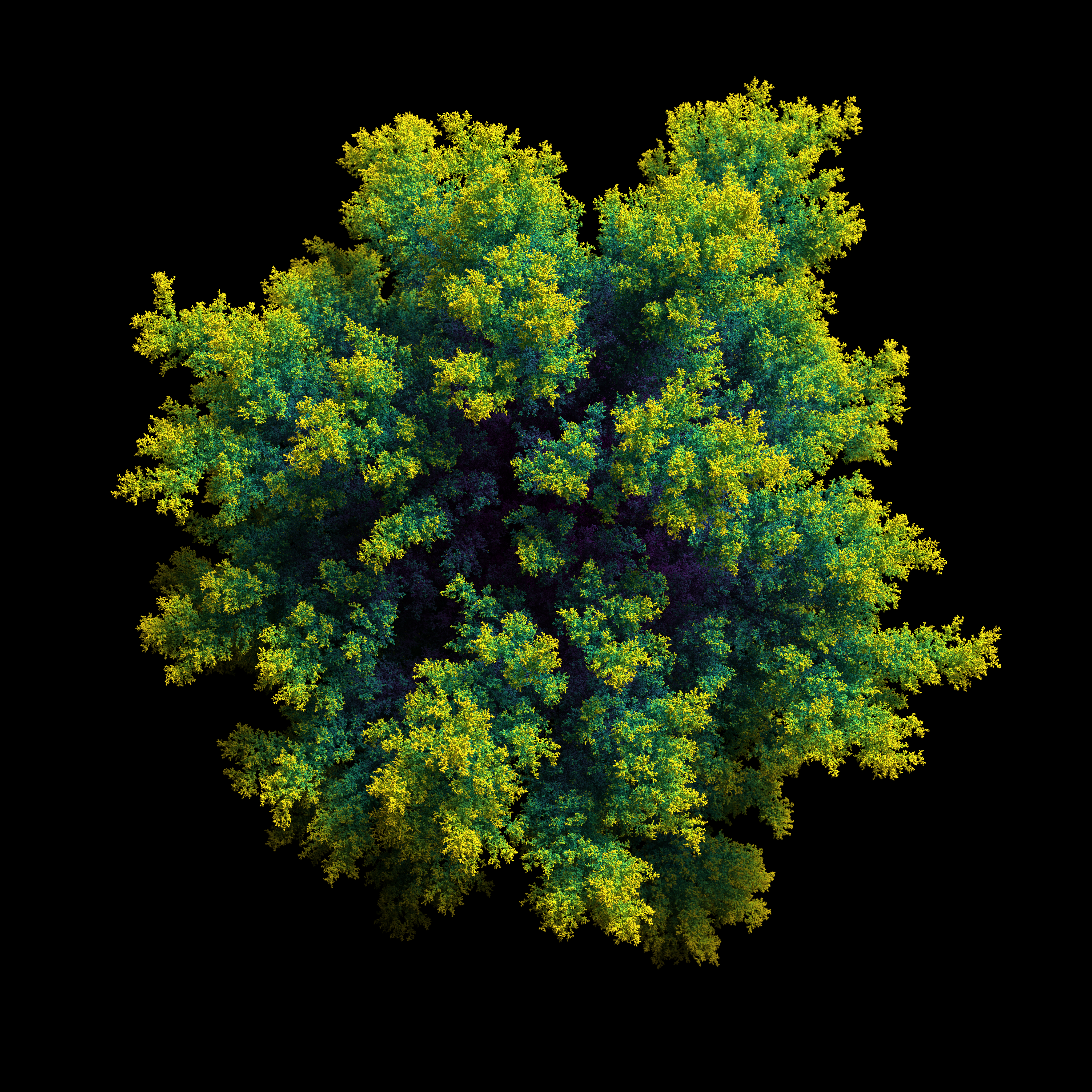

Coming up with interesting scenes that only contain spheres can be tricky, but luckily Michael Fogleman wrote a diffusion-limited aggregation program that can generate beautiful scenes with as many spheres as we want, similar to this one:

Preparation

We are going to start from the path tracer we wrote in the previous post series and update it to only support spheres, a single Lambertian material, and to load the whole scene in global memory.

Fogelman’s DLA generator can generate as many spheres as we need, we are going to focuson 1M and 10M scenes in our tests. Loading the scenes is as simple as reading a csv file, my code is based on the following blog post.

Rendering 1 million spheres at 1200x800 and 1 sample per pixel (spp) took 594s. The renderer was not able to render 10 million spheres as it kept crashing.

BVH

Instead of intersecting each ray with the spheres in the scene, we could build a Bounding Volume Hierarchy (BVH). We are not going into the details of how BVHs work and why they make ray intersection faster as this is covered in much better details in Peter Shirley’s Raytracing the next weekend book. Most of the building and traversal logic are copied as is from the book, and to keep things simpler the BVH is built on the host and copied to the device in one call. The main difference from the book is that we don’t use pointers to store the relationship between nodes and store the BVH tree in a contiguous array similar to the heap data structure.

Another simplification we are going with for now is to keep the number of points a multiple of 2. For a scene of size N we need a BVH tree with a total of N-1 nodes. Each of the N/2 leaf nodes wraps 2 spheres. We store the bvh nodes and spheres in separate spheres and we can use the node_idx to identify if its refering to a bvh_node or a sphere as follows:

if (node_idx < N)

it's a bvh node

else

it's a sphere

Ray Traversal

Assuming we have the following structure:

struct scene {

bvh_node *nodes;

sphere *spheres;

uint count; // N

};

Traversing the BVH tree is done as follows:

bool hit_bvh(const ray& r, const scene& sc, uint node_idx, float t_min, float t_max, hit_record& rec) {

if (node_idx >= sc.count) {

return hit_sphere(r, sc.spheres[node_idx-sc.count], t_min, t_max, rec);

}

if (hit_bbox(r, sc.nodes[node_idx], t_min, t_max)) {

if (hit_bvh(r, sc, node_idx*2, t_min, t_max, rec)) {

hit_bvh(r, sc, node_idx*2+1, rec.t, t_max, rec);

return true;

}

return hit_bvh(r, sc, node_idx*2+1, t_min, t_max, rec);

}

return false;

}

Recursive implementation doesn’t work well on gpu as it requires a stack, per thread, propertional to the depth of the BVH tree and quickly runs out of memory. An iterative implementation is straightforward:

bool hit_bvh(const ray& r, const scene& sc, float t_min, float t_max, hit_record& rec) {

bool down = true;

uint node_idx = 1; // root node

bool found = false;

float closest = t_max;

while (true) {

if (down) {

if (node_idx >= sc.count) { // this is a leaf (sphere) node

if (hit_sphere(r, sc.spheres[node_idx-sc.count], t_min, closest, rec)) {

found = true;

closest = rec.t;

}

down = false;

} else {

if (hit_bbox(r, sc.nodes[node_idx], t_min, closest, rec)) {

node_idx *= 2; // go to left child

} else {

down = false;

}

} else if (node_idx == 1) {

break; // we backtracked to the root node

} else if ((node_idx%2) == 0) { // node if left

node_idx++; // go to right sibling

down = true;

} else {

node_idx /= 2; // node = node.parent

}

}

return found;

}

Results

for a scene of 1M spheres at 1200x800 and 1spp, rendering time went down from 594s to 2s. And a scene of 10M spheres that used to fail is now rendering in 5.5s. Building the BVH takes time though, +18s for 10M spheres.

Using nvprof we can collect a few metrics that can help us confirm what is happening in the kernel. For a scene of 8K spheres we get the following numbers:

| Metric | Description | Without BVH | With BVH |

|---|---|---|---|

| dram_read_transactions | Device Memory Read Transactions | 12,587 | 13,077 |

| gld_transactions | Global Load Transactions | 18,733,000,000 | 924,087,362 |

It’s interesting to see that we 20x less global load transactions because the rays require less data to traverse the whole tree, yet we are still submitting around the same number of memory read transactions most likely because there is less memory coalescing between same warp threads. Even though the kernel is still reading about the same volume of data from device memory, the huge performance boost we get is probably because the ratio of processing vs waiting on memory reads increased thus allowing the device to get more done while waiting for the data to come back from memory (latency hiding).

Here is a link to the full source code.