Lightweight Kernel

Our first, and slow, Cuda kernel

For now, we will be ignoring light sampling, just to make things less complicated, and we’ll add it back later either using explicit sampling or importance sampling.

Uber vs lightweight

We have 2 ways to optimize the rendering using Cuda:

- Move all the logic to an “uber” kernel, or

- Identify which part is the slowest and only optimize that part first, by writing a “lightweight” kernel

Both approaches have their pros and cons:

- writing an uber kernel can be easier because there is minimum communication between the cpu and gpu and the cpu code doesn’t need to change a lot

- writing a lightweight kernel simplifies debugging rendering or performance issues as we have less device code to reason about

- uber kernel will require less data transfers between cpu and gpu

- if your gpu is not dedicated and is also used by the OS to render the display there will be a limit on how long kernels can run. Thus a lightweight kernel will have better chances of fitting in this limit

No approach is a clear winner. We’ll start with the lightweight kernel and we’ll explore the uber kernel in later posts.

Profiling the cpu code

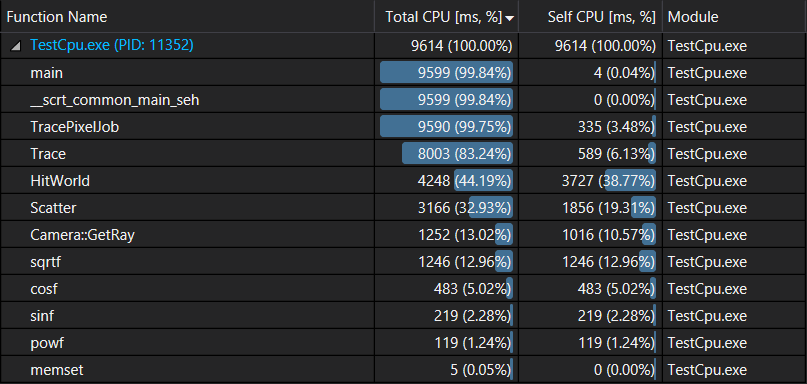

Let’s start by figuring out what takes most of our rendering time. Profiling 10 frames of the application we get the following:

we can see that +44% of rendering time is spent in HitWorld(), this makes it the perfect candidate for our first lightweight kernel

Recursive vs Iterative

Let’s look how current rendering works:

for each frame:

for each pixel:

for each sample:

ray = generate camera ray

color = Trace(ray)

update pixel color in backbuffer

end

end

end

Where Trace(ray, depth) has the following pseudo-code:

if HitWorld(ray):

matE = emission of intersected sphere's material

if depth < kMaxDepth and Scatter(ray, attenuation, scattered):

return matE + attenuation x Trace(scattered, depth+1)

else:

return matE

end

else:

return computed sky color

end

As we can see Trace() is recursive, and that would be fine if we were to write an uber kernel, but we just want to rewrite HitWorld(), so the first step is to make Trace() iterative. The Tricky part is how can we compute final color in an iterative way. The recursive computation goes like this:

C = E0 + A0 x Trace()

where E0 is current matE and A0 is attenuation returned by Scatter. After one iteration:

C = E0 + A0 x (E1 + A1 x Trace())

= (E0 + A0xE1) + A0xA1 x Trace()

After one more iteration:

C = (E0 + A0xE1) +A0xA1 x (E2 + A2 x Trace())

= (E0 + A0xE1 + A0xA1xE2) + A0xA1xA2 x Trace()

We can see a pattern forming up, after each iteration we cumulate the attenuation and emission as follows.

E = (0, 0, 0)

A = (1, 1, 1)

for each depth iteration i:

Ei = intersected sphere's emission

Ai = attenuation returned by Scatter()

E = E + A x Ei

A = A x Ai

end

We can then write an iterative version of Trace() as follows:

TraceIterative(ray)

color = (0, 0, 0)

attenuation = (1, 1, 1)

for depth = [0, kMaxDepth]:

if HitWorld(ray):

color += intersected sphere's material emission

if depth < kMaxDepth and Scatter(ray, attn, scattered):

attenuation x= attn

ray = scattered

else:

break

end

else:

color += computed sky color

break

end

end

return color

Handling all rays at once

Before we can move HitWorld() to the gpu we need to rewrite the rendering logic such that HitWorld() will handle all rays at once one frame at a time. We also need to deal with done rays, we can either compact the list of rays or just mark those rays as done and skip them in HitWorld. We will implement the latter for now. Finally we need to store the individual color/attenuation of each ray between depth iterations. The general rendering logic needs to rewritten as follows:

for each frame:

rays = generate all camera rays (screenWidth x screenHeight x samplesPerPixel)

reset all samples to { color(0, 0, 0), attenuation(1, 1, 1) }

for depth = [0, kMaxDepth]:

HitWorld(rays)

for each ray with index i in rays:

if hits[i].id >= 0:

samples[i].color += intersected sphere's material emission

if depth < kMaxDepth and Scatter(ray, attn, scattered):

samples[i].attenuation x= attn

rays[i] = scattered

else:

rays[i].done = true

end

else:

samples[i].color += computed sky color

rays[i].done = true

end

end

end

end

Convert our Visual Studio project to support CUDA

Let’s start working on the CUDA kernel, I could either create a new project or convert the existing project to also support CUDA. This is easy enough and it’s just a matter of adding “CUDA 9.2” to the project build dependencies:

- right click on the project then select Build Dependencies/Build Customizations

- check “CUDA 9.2 (.targets, .props)”

I will also be using CUDA helper functions, you can find instructions on how to add them to the project in my previous post.

Writing HitWorld() kernel

For now I will be writing the CUDA implementation alongside the cpu implementation as it may come in handy to quickly debug rendering issues. In practice I can just reuse most of the code already written and just extend it to work on both cpu and gpu by adding the following before the function definitions:

__host__ __device__

But as I plan to remove the cpu implementation later, and I’m only going to implement HitWorld() as a kernel, I will add a separate cuda file and copy over all the code needed by the kernel. Before doing so, I will rename the existing float3 struct to f3 so it doesn’t clash with CUDA own float3 as I want to keep the cpu code use as less CUDA code as possible. Again I will be removing it soon enough so this should be fine.

Writing the kernel is simple, most of the HitWorld() code remains the same, but the function now only handles a single ray at a time. Also, because kernel code cannot access host memory we need to copy the rays, and spheres to device memory and hits from device memory for each frame. Here is a link to the full set of changes

Performance improvement (?)

Now is finally the time to run our code and ripe out all the benefits from our hard work. When I run the renderer, it takes its time then finally output the following performance metric:

8.6M rays/s

The code is actually slower than it’s single threaded cpu counter part :(

Well, that was a lot of wasted time here. Or is it ? Luckily for us, CUDA provides very comprehensive profiling tools and in the next post we will be investigating why our first implementation is not fast.