Scatter Kernel

Move more rendering logic to the gpu

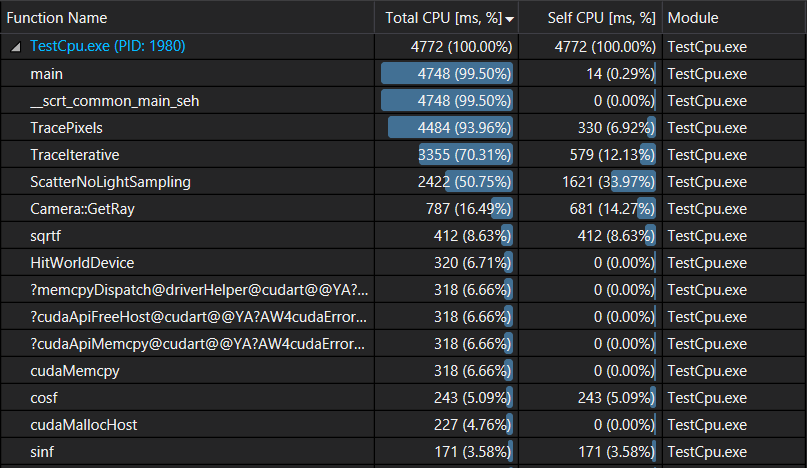

In our previous post we had the following cpu profile:

As we can see, generating the scattered rays is what takes the most of our rendering time. So the next logical step is to move it to the gpu. Once we do that we should move ray generation as well to remove any need to copy data from host to device. After that we won’t really need to compact the non active rays, at least not for now. So we’ll start our work from the version of the code prior to ray compaction.

Ray scattering

As we already described in one of our previous posts here is the pseudo-code for the rendering logic where ray world intersection is handled by the gpu:

for each frame:

rays = generate all camera rays (screenWidth x screenHeight x samplesPerPixel)

reset all samples to { color(0, 0, 0), attenuation(1, 1, 1) }

for depth = [0, kMaxDepth]:

HitWorld(rays)

for each ray with index i in rays:

if hits[i].id >= 0:

samples[i].color += intersected sphere's material emission

if depth < kMaxDepth and Scatter(ray, attn, scattered):

samples[i].attenuation x= attn

rays[i] = scattered

else:

rays[i].done = true

end

else:

samples[i].color += computed sky color

rays[i].done = true

end

end

end

end

Rewriting the scatter logic to work on device isn’t that hard, most of the code will remain the same. But scatter() relies on a simple xorshift pseudo-random number generator. Xorshift relies on a single state variable that’s updated every time we generate a random number. For the cpu code it’s not an issue as we handle all rays sequentially so they can all share the same state, but for the gpu we need a separate state per ray.

The general idea is that we want to generate a random seed from the frame number, and the ray’s Id. I used the following formula which seems to give satisfying results:

uint state = (wang_hash(rayID) + frameID * large_prime_1) * large_prime_2

It’s based on the following course.

Wang hash is motivated by the following blog post

Counting number of active rays

Once we intersect all rays with the scene, we compute how many of these rays are still active, and we use it to track the total number of rays handled by the render. This is mainly used to compute the final performance measure (rays/s).

Once we move the scatter logic to the gpu we will no longer need to copy the hits back to the cpu at the end of each frame, so we’ll have to count the rays in the kernel code. This is not as straightforward as it seems and we’ll leave it for a future post in the series. For now we are going to assume that the number of rays is the same for both cpu and gpu implementations, as we are using the same logic and pseudo random generators.

Writing the scatter kernel

Once we figured out how to compute xorshift state and decided not to count the active rays for now, moving the scatter logic to the gpu is straightforward. Here is a link to the commit. The only reason it’s so big is that we are still keeping the cpu implementation for now so we need to duplicate most of the used functions to use Cuda’s float3 and to mark them as device functions.

Running the renderer we are now getting a performance of 39.3M rays/s. The renderer is 3x faster than the previous implementation, and 5x faster than the original single threaded cpu implementation.

Running nvprof on the renderer we get the following output:

GPU activities: 45.00% 385.73ms 110 3.5067ms 1.0550ms 17.244ms ScatterKernel(DeviceData, unsigned int)

27.66% 237.08ms 110 2.1552ms 1.1633ms 5.1389ms HitWorldKernel(DeviceData, float, float)

18.86% 161.66ms 10 16.166ms 15.089ms 17.079ms [CUDA memcpy DtoH]

8.49% 72.773ms 12 6.0644ms 608ns 8.0377ms [CUDA memcpy HtoD]

API calls: 78.64% 860.78ms 22 39.127ms 71.841us 91.112ms cudaMemcpy

14.03% 153.61ms 2 76.803ms 8.1760ms 145.43ms cudaMallocHost

4.87% 53.304ms 1 53.304ms 53.304ms 53.304ms cuDevicePrimaryCtxRelease

1.15% 12.587ms 2 6.2935ms 3.3327ms 9.2543ms cudaFreeHost

0.92% 10.023ms 5 2.0045ms 13.493us 3.8852ms cudaMalloc

0.14% 1.5626ms 4 390.66us 49.595us 623.59us cudaFree

0.12% 1.3325ms 220 6.0560us 3.6460us 35.373us cudaLaunchKernel

0.08% 917.88us 40 22.947us 364ns 487.20us cuDeviceGetAttribute

0.04% 483.19us 1 483.19us 483.19us 483.19us cuModuleUnload

0.00% 34.644us 1 34.644us 34.644us 34.644us cuDeviceGetName

0.00% 9.8470us 1 9.8470us 9.8470us 9.8470us cuDeviceTotalMem

0.00% 8.3880us 1 8.3880us 8.3880us 8.3880us cuDeviceGetPCIBusId

0.00% 2.5520us 3 850ns 364ns 1.8230us cuDeviceGetCount

0.00% 1.0940us 2 547ns 365ns 729ns cuDeviceGet

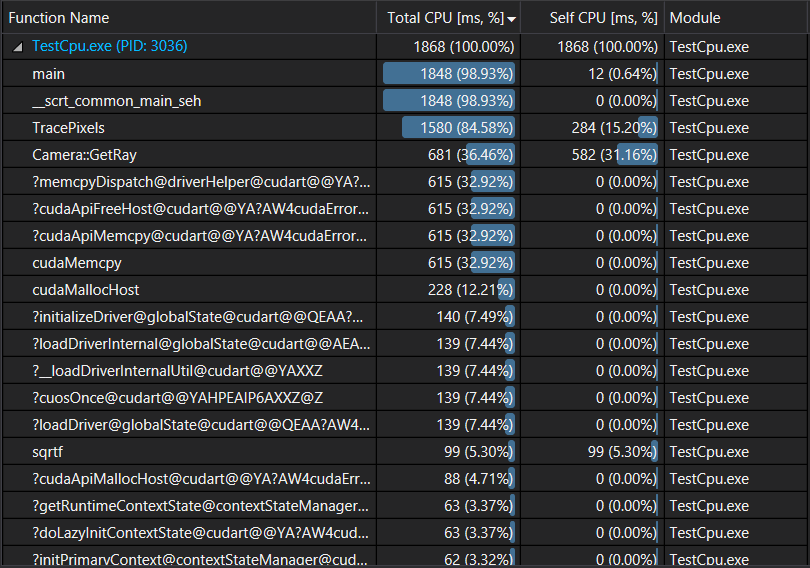

We can see that most of the time is now taken by the kernels, as we are no longer copying huge amounts of data between the host and device. Cpu profiler shows the following:

Looks like the slowest part is now the camera ray generation as it takes 36% of the rendering time. There is no reason not to move it to the gpu as well as it will also remove the need to copy the rays to gpu at the start of each frame.

Generate rays on gpu

Moving ray generation to the gpu is not complicated. We add a new kernel that will generate the rays using a xorshift random state initialized as we described before. Most of the changes involve refactoring the renderer code to handle both cpu and gpu rendering. Here is a link to the commit.

Rendering performance went up to 86.5M rays/s. The renderer is nearly 11x faster than the original single threaded cpu implementation.

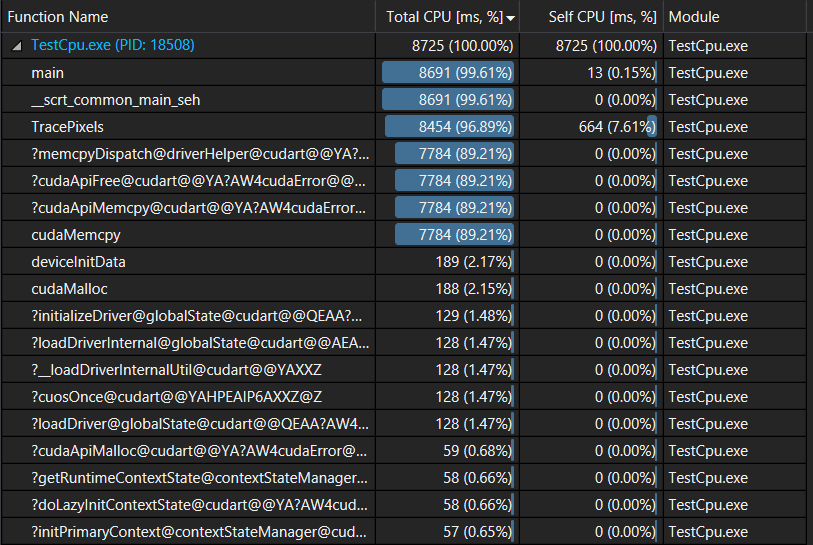

A look at the cpu profile shows that 90% of the time is now spent in the kernels:

and nvprof show that Scatter kernel takes nearly 50% of the device time:

Type Time(%) Time Calls Avg Min Max Name

GPU activities: 46.36% 3.75411s 1100 3.4128ms 1.0449ms 17.251ms ScatterKernel(DeviceData, unsigned int)

28.36% 2.29702s 1100 2.0882ms 1.1570ms 5.1423ms HitWorldKernel(DeviceData, float, float)

19.70% 1.59537s 100 15.954ms 14.254ms 29.381ms [CUDA memcpy DtoH]

5.58% 451.68ms 100 4.5168ms 4.4661ms 5.7258ms generateRays(DeviceData)

0.00% 2.3360us 3 778ns 576ns 1.0560us [CUDA memcpy HtoD]

API calls: 97.67% 8.11370s 103 78.774ms 75.122us 95.287ms cudaMemcpy

1.58% 131.13ms 6 21.855ms 8.7520us 120.89ms cudaMalloc

0.52% 42.936ms 1 42.936ms 42.936ms 42.936ms cuDevicePrimaryCtxRelease

0.20% 16.210ms 2300 7.0470us 3.6460us 98.826us cudaLaunchKernel

0.02% 1.5685ms 5 313.69us 32.091us 642.92us cudaFree

0.01% 981.70us 51 19.248us 364ns 466.42us cuDeviceGetAttribute

0.01% 435.42us 1 435.42us 435.42us 435.42us cuModuleUnload

0.00% 35.373us 1 35.373us 35.373us 35.373us cuDeviceGetName

0.00% 28.809us 1 28.809us 28.809us 28.809us cuDeviceTotalMem

0.00% 8.3880us 1 8.3880us 8.3880us 8.3880us cuDeviceGetPCIBusId

0.00% 2.5530us 3 851ns 365ns 1.8230us cuDeviceGetCount

0.00% 1.0930us 2 546ns 364ns 729ns cuDeviceGet

Conclusion

It took us some time but we are finally at a point where most of the rendering time is spent on the device, which means in the next blog posts we’ll start exploring how we can optimize the kernels.